|

This article is republished with the kind permission of the original author, Barry Meadow.

Barry is the author of MONEY SECRETS AT THE RACETRACK, THE SKEPTICAL HANDICAPPER, and MEADOW'S RACING MONTHLY among several other excellent works. Have a look at his website here: TRPublishing.com

THE SARTIN METHODOLOGY: UNRAVELING THE MYSTERY

Originally published in Meadow's Racing Monthly, October 1997 - images added by S&HR

Trying to discern the truth about Howard Sartin and his Sartin Methodology is like trying to capture a moonbeam. It looks easy enough, but as you get closer to it, you realize it’s a very elusive thing.

Trying to discern the truth about Howard Sartin and his Sartin Methodology is like trying to capture a moonbeam. It looks easy enough, but as you get closer to it, you realize it’s a very elusive thing.

First one guy tells you an amazing story. Then a second guy denies that the first thing ever happened, but here’s an even wilder tale. Then a third guy comes along who tells you that both the first two fellows are liars.

It’s a strange story that gets stranger and stranger as you get deeper into it.

Just for starters: The man who is known to the handicapping community as Ph.D. psychologist Howard Sartin has a mail-order Ph.D. and is not a psychologist.

Sartin has been called a “con man and a fraud,” by Tom Hambleton, one of Sartin’s co-authors of the book Pace Makes The Race. He has also been called “a brilliant man of considerable integrity” by Tom Ainslie, perhaps the best-known handicapping author of our time.

As for the Sartin computer programs, they are—depending on whom you talk to—either a rehash of basic pace analysis with occasional cosmetic changes, or an ever-increasingly sophisticated handicapping method that is the leading edge of the game today.

Is Sartin is simply a colorful character who maybe exaggerates things a little but nonetheless produces terrific handicapping programs? A money-grubbing charlatan who has tricked people into thinking he’s a genius? Neither? Both?

To find out about Sartin and the Sartin Methodology, I interviewed more than two dozen people who were familiar with the man and his programs. I talked with instructors who made presentations with him, players who’ve used the software, and computer programmers who’ve studied the codes. I talked to those who’ve been Sartinites for a dozen years and are extremely satisfied, and to disgruntled ex-followers.

What emerges is a complex and contradictory portrait of both the man and his work.

The first printed reference I could find to the Sartin Methodology was an article by Sartin that appeared in the March 1982 issue of Gambling Times. In it, he related the origins of his method and he made some astonishing claims.

According to Sartin, in 1975 he was asked to counsel a group of truck drivers who had been convicted of offenses related to their gambling problems. Rather than advising abstinence (such as Gamblers Anonymous would suggest) or trying to get to the underlying root of the problem (as conventional therapy might offer), Sartin says he came up with the idea that the problem was not necessarily that these people gambled, but that they lost. If they had been winning gamblers, they would not have gotten into trouble. Thus came the essential core of Sartinism: “The cure for losing is winning.”

In this pursuit of success, the story continues, he and the group studied every handicapping method there was and found validity in some of the work on pace that had been done by such pioneers as Ray Taulbot and Huey Mahl. Sartin further refined some of these techniques, which became the basis for the Sartin Methodology.

In the article, Sartin stated that, “My practice is limited to so-called horseplayers and a client is cured only when his top choice is winning no less than 45% of the time with an average mutuel of $8.”

Doing the math, this works out to an ROI of 80%. If someone were to bet $2,000 a day and played five days a week, he would earn $400,000 per year betting the horses. You would think that such claims would have been met with skepticism from the handicapping community, but nobody ever seems to have checked them out.

And as the years went on, the claims continued and expanded. According to James Quinn in The Best Of Thoroughbred Handicapping, published in 1987, Sartin’s study groups found the two-horse method [betting two horses to win in a 60-40 ratio] produced 64% winners at an average mutuel of $10.80. This would equal an ROI of 72.8%. Again, if the numbers were true, anybody betting sizeable amounts of money could easily have earned millionaire status in a short time.

Yet Quinn, who now says the numbers were provided by Sartin (his daughter says they were compiled from reports from customers), told me that once he gave a talk at a Sartin seminar in front of several hundred people and asked players to raise their hand if they’d made $20,000 or more at the races the previous year—and not a single hand went up. (Then again, maybe people might have bought the programs, began to win with them immediately, and never felt the need to attend a seminar at all. Or maybe winning players preferred to remain anonymous.)

Interestingly, Sartin no longer makes such claims. “Clients and non-clients alike ask what average mutuel they should expect,” writes Sartin in a recent issue of his subscription publication, The Follow Up. “This is an extremely naive question... The very nature of the question makes me fear for the asker’s state of mind. My fear comes from knowing that anyone asking such a question and believing any answer is setting himself up to be taken in by the claims and promises of charlatans.”

Was the truck driver story true? Who knows? Sartin’s business name, Inland Empire Institute, was not registered in Riverside County until 1982.

One time at a seminar, Sartin did introduce a man as a “member of our original group.” According to Tom Hambleton, “In the hallway, I talked to the guy for a minute. He said that what happened in his group was nothing like what Howard described.”

Hambleton, though, is not exactly an unbiased witness. An early member of PIRCO (Pari-Mutuel Investment and Research Company), the teaching group that Sartin formed in 1982, Hambleton worked with Sartin for years before becoming disillusioned after the publication of Pace Makes The Race. He now makes no secret of his disdain for Sartin.

Ah, Pace Makes The Race. This book, published in 1992 by Sartin’s O. Henry House, Inc., was a turning point for the Sartin Methodology. There were three co-authors listed for the book besides Sartin—Hambleton, Dick Schmidt, and Michael Pizzola. The four of them had shared many hours on the podium at seminars, disseminating the Methodology.

The actual contract was between Sartin, who was to have received 30% of the book’s net proceeds, and Schmidt, who was to divide his 70% share with the two other men. The printing of 6,000 copies sold out, at prices ranging from $17.97 to distributors to $29.95 for full retail. Allowing for printing, marketing, and distribution expenses, it’s likely that the net profit was at least $70,000, which would have meant at least $16,000 for each of the co-authors.

Here’s where it gets tricky, with he-said she-said overtones and charges of “Hollywood accounting” where a CD sells a zillion copies but the company claims it lost money. Schmidt paid Hambleton approximately $27,000. But Hambleton says about $25,000 of that was for royalties for computer programs he had written, so his share of the books profits was just $2,000 — the only money he received for, essentially, writing the largest portion of the manuscript.

Pizzola, meanwhile, was having his own disputes with Sartin over Pace Makes The Race. Schmidt paid Pizzola about $10,000, though again this was apparently co-mingled with other payments due.

It appears that Sartin did pay Schmidt what he felt was the correct amount of money, and Schmidt then did pass on their shares to Hambleton and Pizzola. However, Sartin may have charged to expenses higher amounts than what the other authors thought was fair.

Though Pizzola had no written agreement with Sartin, he blamed Sartin for, essentially, holding back revenues that he thought should have flowed to him through Schmidt. Pizzola, who had been a lawyer before getting full-time into the handicapping business, struck back at Sartin in what some might call a cruel and vindictive way. Though he neither confirms nor denies that he was the man behind it, Pizzola does admit that the banana incident was “deliciously theatrical.”

In the middle of a seminar at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, several dancers burst into the room dressed like Chiquita Banana. They then began singing “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” while tossing flyers around the room that charged Sartin with everything but killing the Lindbergh baby.

After the initial shock had worn off, the instructors quickly gathered and tossed the flyers. Tom Brohamer then stood up and gave Sartin a moving tribute. The seminar continued, though everyone seemed a bit shaken.

Some say that Pizzola, who is best known for co-developing the Master Handicapper computer program, was simply a troublemaker who tried to horn in on a successful business that Sartin had worked so long and hard to build.

Pizzola later sued Sartin for damages, in a federal court located in New York where Pizzola then lived. But no matter whether or not the suit had any merit, it would have been very difficult for Sartin, who lived in California, to defend against it. To avoid this, Sartin was advised to declare bankruptcy in California.

Such a move meant that before anything could happen in New York, Pizzola would have had to prove his claims in a California bankruptcy suit. In a Chapter 13 filing on Feb. 22, 1993, Sartin stated that he had assets of $206,914 with debts of just $10,354 — which makes it seem pretty clear that the bankruptcy was filed simply to escape the lawsuit, which Pizzola then dropped. According to Sartin’s lawyer, Steven Dolan, “All of Dr. Sartin’s creditors were paid off within a short period of time at 100% on the dollar.”

Although all four names were on the original notice of copyright, Hambleton and Schmidt went ahead and republished the book under Schmidt’s Eighth Pole Press, listing only themselves as copyright holders and removing all material written by Sartin and Pizzola. Was this legal? Not really, but Hambleton and Schmidt apparently figured that this was their best hope to try to make some of the money they thought was due them in the first place.

They also removed all references to their original co-authors. In a section called The Configuration Of A Race that talks about determining how a race will be run, for instance, the original version said, “In PIRCO, Tom Brohamer first incorporated this traditional racing concept, and Dr. Sartin refined it.” The republished version says, “Tom Brohamer taught us this traditional racing concept.” It was like one of those Russian history books where the guy who fell out of favor simply ceases to exist.

Hambleton, Schmidt, and Pizzola no longer talk with Sartin. When Sartin found out that I had interviewed Pizzola and Hambleton, along with some other people who are no longer associated with the Sartin programs (Schmidt is in England and was unavailable for comment, though we did obtain a copy of the book contract), he wrote me, “[I’m] amazed that you are seeking out persons who feathered their nest with my work and made more money than I selling it under their own label. Only two of them have maintained any integrity and honor — Tom Brohamer and Jim Bradshaw. The rest...are just hustlers who follow the Pygmalion pattern of turning on their mentor...”

There are two major areas a researcher needs to look at when studying Sartin and his Methology. The first is to figure out who Sartin is, and how he became a star of the handicapping world. The other area, more important, is to look at the programs themselves to see whether they do what they say they will do.

Figuring out who Sartin is has turned out to be an exercise in futility. In none of Sartin’s own material that I’ve read — nor in the writings of anyone else I could find — is there any reference to Sartin’s hometown, early years, schooling, work experience, or anything else. He seems to have appeared out of nowhere in 1982, when he wrote the Gambling Times article and a letter to Phillips Racing Newsletter describing his work, formed PIRCO, and registered the name Inland Empire Institute.

What did he do before that? No one seems to know.

When he learned I was researching this article, Sartin sent me a note, as well as a recent edition of The Follow Up (a subscription publication of the Methodology) and a copy of the Official Sartin Methodology Today Workbook. I called him and said I wanted to meet with him to review some of the questions I had both about him and his work. He enthusiastically agreed, saying I could come up at any time. We made an appointment for 10 a.m. the following Monday.

But two days before the interview was to take place, I found this message on my answering machine, from Sartin: “This is Howard Sartin. On the advice of my attorney based on the nature of some of the questions you asked Tom Ainslie and Jim Bradshaw, he said I should not talk to you. Cancel the Monday appointment.”

While rumors about Sartin’s earlier years are legion, pinning them down has proved daunting. While it’s far from clear who Sartin is, one fact did emerge — he has never been licensed to practice psychotherapy in California.

To practice therapy of any sort in the state normally requires a license, but the law has enough loopholes so that someone calling himself an addictions counselor, for instance, is not doing anything illegal as long as he does not claim to hold a license that he does not have. How, exactly, did Sartin come to treat the truck drivers? That’s one of the many questions I wanted to ask him.

But who Sartin might be is, ultimately, less important than the work he’s done. Let’s say that I teach high-school French and I’m good at it. I also claim that I’ve climbed Mount Everest and pitched in the World Series. Even if the latter assertions are untrue, I still remain an excellent teacher of French. And if French is what you’re studying, does it really matter that I’ve told a couple of unimportant fibs about other things?

In Sartin’s case, maybe, maybe not. Most of what he’s presented at his own seminars have been lectures about the psychology of winning.

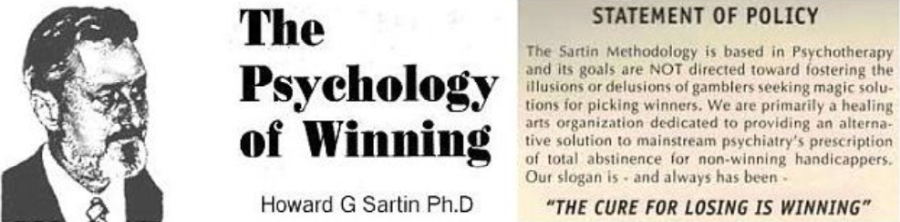

He’s even written a 73-page booklet called The Psychology Of Winning: An Introduction To Win Therapy. Throughout the booklet, Sartin pays homage to well-known names in psychotherapy. Open any page and you can find references to adult ego state, repetition compulsion, the drama triangle, and many other terms from psychotherapy. The impression — though it is never stated anywhere in the material — is that Sartin is a serious student of how gambling and psychology are connected, and has long experience with problem gamblers.

True? False? True with an asterisk?

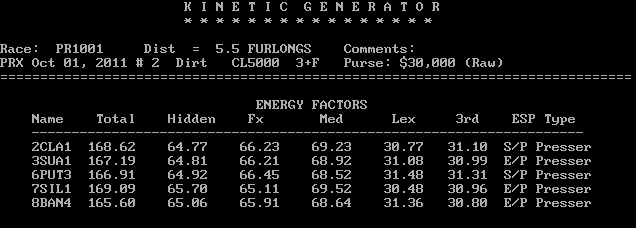

Generally, the computer programs look at the relationships between various race segments using feet-per-second measurements and compounded pace ratings. The basis for most of Sartin’s programs has been inputting a single paceline for each contender into the computer. Each of the programs then massages the numbers — usually by breaking each horse’s paceline into various segments and permutations—and comes up with a variety of readouts.

Most are designed to compare a horse with what the probable pace of the race is going to be, based on the entrants in this particular race. Who figures to have the lead early? Will he be able to hold it by the second call? Who has the best closing speed? How does each horse’s pace profile stack up against recent winners at this track and distance?

The programs ignore class, par times, trainers, jockeys, layoff patterns, workouts, and other staples of traditional handicapping. There are no references to such angles as equipment changes, lasix, or breeding. And by emphasizing pace ratings and comparisons, rather than final-time numbers, sometimes the horses with Sartin’s best numbers are overlooked by the public.

Sartin’s theory is that the most important handicapping factor is to measure not just a horse’s speed, but how a horse accomplishes what he does. The programs depend on several assumptions — that a horse will replicate a particular previous performance, that a player can determine which running line in a horse’s past the horse will repeat, that the other entrants will run back to their own performances, and that other handicapping factors are basically extraneous.

The idea of projecting possible improvements (trainer change? distance switch? trouble last start? first-time lasix? improved workouts? third start off a layoff?) is rejected as simply guessing. Rather than guess, why not look at what the horse has actually done? Rather than try to look at every factor under the sun, much of it conflicting, why not focus on black-and-white numbers that are based on fact and that can be computed?

Using the programs has been anything but simple, though his latest versions, Pace Launcher IV and the upcoming Pace Launcher V, seem more user-friendly than most. Both Sartin’s supporters and critics generally agree that the early programs, and their accompanying manuals, were hard to understand and difficult to use. Carroll Pfrommer, a California player who has high praise for the Methodology, says, “I’m not a typist and for me to sit down with a Racing Form to pick out the paceline, enter the data keystroke by keystroke, print it out, analyze and interpret it, make decisions — we’re talking an hour a race with four or five pages of printouts.”

While velocity ratings had been mentioned in the racing literature for decades, and the selection of a paceline was a staple of methods published by (among others) Taulbot, some of the other parts of the Methodology were original.

“I think they’ve made some real contributions to pace analysis and pace ratings,” says Quinn. “Relating the energy distribution requirements to the particular track and distance was a breakthrough.”

The latter area—calculating that a particular horse figured to use 51.3% of his energy early but since most of the winners at a certain track for a particular distance used only 47.9% of their energy early, he figured to tire—has generally been credited to Brohamer, a frequent participant in the Sartin seminars who would eventually go on to write Modern Pace Handicapping and supervise the development of the software of the same name.

“I still acknowledge a debt I owe to Sartin,” says Brohamer, who’s now retired. “My lifestyle changed as a result of being involved with him. It took Howard to convince me that I had an aptitude for this. He made me realize that I could do it. Without Howard and PIRCO, I’d probably have kept working for the phone company. It changed my whole career path.’’

An early client, Brohamer asked Sartin whether the Methodology could be programmed into a hand-held computer. Sartin said it couldn’t. But Brohamer, a self-taught programmer, worked on the problem and solved it. Sartin then invited Brohamer to join the group as an instructor.

At the time, the Sartin Methodology was relatively new and the group consisted of handicapper-hobbyists who came together to try to improve their bottom line at the track. Few players owned personal computers, and nobody could have predicted that within a couple of years, crowds in excess of 200 would pay $250 or more to attend a Sartin seminar.

How did the Methodology become so successful? It was a combination of things. The wild claims were made not by an anonymous mail-order pitchman but by a seemingly respected professional, and this attracted many of the curious. Because much of the written material was difficult to understand, players would religiously attend seminar after seminar (at $30 to $275 apiece), hoping to grasp such arcane concepts as deceleration ratios or average energy distribution. Sartin himself was a spellbinding speaker. The other presenters seemed knowledgeable about other areas of handicapping.

And there were always new programs to buy, and learn. Among the programmers was a former teacher and track coach named Jim “The Hat” Bradshaw, who remains a Sartin ally to this day (Note: Bradshaw’s new book, The Match Up, is reviewed on page 18).

“I met Howard at a seminar in New Orleans more than a dozen years ago,” says Bradshaw. “I had tried everything to try to win at the races, but I had never thought about pace. Once I started going through Howard’s material, I felt that pace was the way to go. I started with a calculator using raw fractional times.”

Like Brohamer, Bradshaw taught himself how to write computer programs. When Sartin said he needed someone to work on translating his ideas into computer code, Bradshaw became one of the main contributors to the Methodology.

“I started writing on a VIC-20 which was similar to the old Commodore,” Bradshaw recalls. “I wrote the Energy program on a Radio Shack computer, and finally graduated to programming for IBM computers.” Bradshaw also wrote the KGEN and Thoromation programs, among others. “I think that Howard is not only a great person, but he’s really advanced the teaching of handicapping,” Bradshaw says. “And the programs have made a winner out of me.”

“Our concept differs from mainstream logic in that we handicap the race, not just individual horses,” Sartin writes. “It is not how fast a horse can run that counts most, but how well it can run relative to the fractional velocities projected by today’s matchup.”

Ainslie has nothing but praise for Pace Launcher, the newest program. “Sartin’s latest piece of software is, as usual, light years ahead of the previously best,” he says. “Unlike some of his previous software, this one does most of the work for you. I’ve been making money with the Methodology for years. I’ve found it helpful from the get-go.”

Using the programs correctly, as Sartin points out, requires a player to have two skills—the ability to pick the contenders (Sartin discourages players from inputting information on every horse in the race, saying it gives misleading outputs), and the ability to select the paceline which best reflects the horse’s chances today. Most seminars attempt to show players how to accomplish these tasks. Generally, Sartin’s contribution to the seminars has been to discuss the psychological side of becoming a winning player.

This is curious, because by all accounts Sartin rarely gambles. While many of the seminars have been held in hotel rooms and have concentrated on past races, sometimes a seminar would be held at a racetrack or in a racebook; the handicappers would comment on upcoming races and then bet them that day. At the track, Sartin would occasionally buy $2 tickets on several—sometimes all—horses in a race. And when some hapless attendee would lament that he had bet on one of the losers, Sartin would sometimes pull a winning ticket from his pocket and give it away to the student.

While he could discourse about pace, Sartin seemed to know or care little about other aspects of handicapping. He’d quote statistics that were simply made up, but rarely was a dissenting peep heard. “If you challenged him on anything, he’d get reactive,” says one man who’s worked with him. “He had gurutis, like how could he possibly be questioned on anything?”

The typical seminar had a variety of speakers, each with his own topic. Sartin might talk about psychology, Pizzola about paceline selection, Hambleton about total pace ratings, Bradshaw about the matchups, and Brohamer about energy distribution. Guest speakers would appear from time to time. At the major seminars, there would often be a new program for sale.

“You always had to have the latest one,” says one former Sartinite, “or you’d be left in the Dark Ages of handicapping. Imagine a plane that you could never fly because they were always changing the dials in the cockpit—that’s what it was like.”

In both his writings and on stage, Sartin would toss around such terms as vector magnitude, chaos physics, the variegate screen, entropy, and other concepts which had meaning to almost nobody. Were these brilliantly conceived ideas that were difficult to explain to laymen, or simply big words signifying nothing? “Mathematics is a funny thing and so is semantics,” says one observer, “and Sartin would toss them both around very casually.”

“Einstein couldn’t have understood the material,” said one man who’s shared the podium with Sartin. “The manuals were disorganized and confusing and the materials so contradictory it’s a joke. If the stuff was so clear, we wondered why people always had to go to the seminars.”

The reason, some charged, was that Sartin had a master plan which one speaker described as “Keep them dumb and keep them coming.” Because if you could actually understand everything and replicate it step-by-step, there’d be no reason to constantly attend seminars and buy new programs. With a bewildering variety of screens and readouts to study, it wasn’t difficult to say that you would have picked the winner if only you had chosen the sustained pace readout in this race, or the third race back paceline in that one, or the valence screen over here.

And most of the time, the handicapping lessons were based on races that had already been run. When the leaders did review upcoming races, each usually discussed it in terms of how he handicapped the race, not how the program should be used to make the selections.

The programs have profilerated. Among them: Kinetic Generator (KGEN), Entropy, Selector, SPN, Fractals, Quad-Rater, Phase III, Thoromation, Chaos, Synergism, Ultra Scan, and Energy. Several of these have more than one version. Some offer printed tables of numbers, others show horses galloping across the screen, others include pie charts, some use bar graphs.

The most up-to-date version of Pace Launcher includes the capability of downloading files and having the program pick the paceline, as well as an odds line for easy detection of overlays (though no one knows how effective or accurate it is). This downloading capability—a standard feature in most non-Sartin programs—figures to mean additional sales. The programs and seminars have accounted for some very big money over the years. Hambleton wrote some programs to calculate total pace ratings and says, “We must have sold a thousand of them at $100 to $165 apiece.” The major weekend seminars, held in various cities, routinely attracted crowds of 200 or more players who paid $250 to $275 to attend.

And while guest speakers might have been paid $1,000 for the weekend, most of the teaching members through the late 1980’s generally participated for expenses only—and made no demands otherwise. After all, most of them originally came in as students, and gained a measure of pride and sometimes fame by being promoted by Sartin to “teaching members.”

In some years, the organization took in hundreds of thousands of dollars, though much of that went for salaries to the office staff (most of whom were, and are, Sartin’s family members), royalties to programmers such as Bradshaw and Hambleton, and seminar expenses.

Little money was spent for advertising or direct-mail campaigns, yet people were clamoring for the material. And the fact that Sartin didn’t seem to want to build an empire might have made it seem even more attractive.

“Here you had an organization that told you that what they were teaching you was difficult, only the really smartest of the smart could understand it, and that they didn’t need your money anyway,” says Hambleton. “Sometimes people would send Howard money for a program, and he’d send back their check and tell them they weren’t ready for that particular program yet. Naturally this made them even more eager for the material, and Howard would wind up bleeding them dry. It was exactly like Scientology.” At one point, Sartin was requiring students to send in a list of their last 20 plays before he’d sell them the next program; at seminars, students were privately begging the other teachers to let them purchase it.

“You have to understand the art of seduction,” says Phil Gowens, who’s been associated with the Methodology as both student and teacher and who is an executive trainer. “People would come to a seminar and see their heroes on stage. They’d have a belief that someone is going to help them, and here’s the product that can do it. In a group situation, where there’s little questioning going on, it’s very difficult to resist. People buy things on emotion, not because of rational thought, and the atmosphere fostered that. I saw a circus, and I don’t mean that in a negative way. Doc runs a good show—there’s a lot of entertainment involved. I learned a lot about human behavior from these seminars.”

Many of the teachers paid little heed to money. And sometimes, it seemed, neither did Sartin. He’d sometimes let players attend seminars for free. He’d treat the whole teaching crew to dinner. If a speaker wanted his wife’s expenses covered, Sartin would do it. If somebody said he was down on his luck, Sartin might hand him a thousand dollars and never ask for it back. At his office, Sartin would sometimes spend hours with customers reviewing the programs without charging them a dime.

But some instructors began to feel that while Sartin seemed free with a dollar, it was only because he had plenty of dollars to be free with. Dollars that they had helped to bring in—and were not going to them.

I tried again to speak with Sartin, driving to Beaumont, the working-class desert community 75 miles from Los Angeles that’s home to the Sartin Methodology, and calling his office. Sartin reiterated that on the advice of his attorney he wouldn’t be able to talk, but his daughter, Mary, met me at a nearby coffee shop.

The Sartin enterprise has five employees besides Sartin—his wife Mary, his daughter (also named Mary), his son Shane and his wife, and a family friend who supplements her social security income. “My father wanted this organization to be self-supporting,” Mary told me, “but he never got into this to become rich. Anybody who thinks that doesn’t know very much about him.

“I’ve been trying to get him to raise the price for The Follow Up, and to charge people when they spend several hours with him when they have questions about a program, and he won’t do it. He’s always told us that what’s important to him is that we help our clients to be successful. I’ve got a 1989 Nissan Maxima with 215,000 miles on it and a crack in the windshield. If my father got so rich on all this, where’s the money? I don’t know, and I’m the bookkeeper.”

Just recently, Sartin agreed to endorse the TrackMaster computer service—and though payment for such an endorsement is standard, according to the company’s Ellis Starr, “Sartin had lunch with us, said he liked our programs and would endorse them, and didn’t ask for a penny in return.”

Pizzola tells a familiar story about how he got involved with the Sartin Methodology. “Horse racing was a passion for me, and I saw an article in Phillips Racing Newsletter about how great the Sartin material was. There was this terrific story about how Howard was trying to help degenerate gamblers, and I thought, how wonderful. In my naivete, I really did buy in that he was trying to help people. I believed in him.”

Pizzola taught at the seminars for several years, discussing such topics as pace matchups, selecting pacelines, how to make adjustments by hand, and how to interpret the program readouts. “I never doubted the techniques we taught,” he says. “But I began to see it as a cult. More and more at the seminars, I’d see and hear things and begin scratching my head.”

The word “cult” was used by a number of people I interviewed. Most cults contain five common elements—a charismatic leader who seems to have special insights and whom the followers treat with devotion, a discipline that fosters the idea of his inerrancy and discourages questioning of his ideas and methods, a siege mentality of us-against-them that discourages contact with non-members, a jargon (private language) that cannot easily be understood by outsiders, and a constant stream of new revelations from the leader that require group members to spend money and/or time to attain the next level. The Sartin Methodology seems to have had, in some measure, all of these attributes. The word “cult” was used by a number of people I interviewed. Most cults contain five common elements—a charismatic leader who seems to have special insights and whom the followers treat with devotion, a discipline that fosters the idea of his inerrancy and discourages questioning of his ideas and methods, a siege mentality of us-against-them that discourages contact with non-members, a jargon (private language) that cannot easily be understood by outsiders, and a constant stream of new revelations from the leader that require group members to spend money and/or time to attain the next level. The Sartin Methodology seems to have had, in some measure, all of these attributes.

Among the things Pizzola and others said they’d wince at was the sometimes savage way that Sartin would handle questions. “That’s a dumb question” was a frequent answer. One problem was that the seminars included both people who could barely read a Racing Form and players who had years of experience with the Methodology.

Another trouble spot was Sartin’s bizarre and frequent charge that if a player picked the “wrong” paceline for a race — that is, the horse didn’t win but had you selected a different line the horse might have been ranked first on a readout — the player was a losing gambler who needed “re-parenting.”

Says one former instructor, “The attitude was that if you had the winner, the program picked it. If you didn’t, it was your fault. People were intimidated. Imagine yourself in a large room, filled with bright people, led by bright people, and you didn’t understand something. You’d be thinking that you were the idiot.” And if you’d just spent several hundred dollars on computer programs and seminars, you’d have a powerful incentive to try to make it all work—and to blame yourself if you didn’t win.

Thoughout Sartin’s years in the game, which he describes as “helping people become winners, rather than simply helping people pick winners,” he’s constantly stressed to players that they must believe in themselves. If you lost, maybe it was because you wanted to lose. The cure for that would be twofold—buy his computer programs which would enable you to land on the right horses, and get your attitude straight.

But, as with any handicapping plan, some people say they’ve done well with the Methodology while others say they couldn’t win with it. As for thinking positive, a wise guy once observed that you can say “I am tall, I am tall” a hundred times a day—but if you’re a midget, you’re still short.

Sartin’s stated goals—and hyperbole—haven’t changed much over the years. In a recent issue of The Follow Up, he wrote, “Our first goal is to win all the races paying double-digit win mutuels at Hollywood Park and Golden Gate. Thus far, in 96 races, we’ve missed five double-digit winners.”

Sounds too good to be true, as have other claims. He tells, for instance, of originally developing the Methodology on a large database. According to a note sent by Mary Sartin shortly after our meeting, “There were six full-time clients who put races through the various Sartin formulae of that time. They each did five races per day with a hand-held calculator using the Methodology of that early period. The results were analyzed on a mainframe computer...The compilation went on for seven years (49,000 races).” But the numbers were also reported as 25,000 races by Quinn (1987) and 18,000 races by Brohamer (1991), though both told me they had gotten the numbers from Sartin and had never actually seen the data.

While there’s no doubt that some customers worked a number of races and reported the results to Sartin, the claims raise more questions than they answer. How many races were there? Who did them? Under what conditions? Using which programs? Who checked them? And on and on.

At Handicapping Expo 93, where Sartin and I both spoke, I ran into him at the Mirage racebook. Here is Sartin’s account, as it appeared in The Follow Up:

“[Barry] studied one of the Mirage’s giant TV screens until a horse crossed the finish line first. Barry calmly held up for my view a win ticket on that horse worth several thousand dollars. He then produced two more tickets whose combined worth equaled the first...In a relatively short period of time he had wagered thousands of dollars [and] won even more.”

What actually happened was that I had made a small bet, part-wheeling an exacta, and collected only a few hundred dollars. After seeing the report in The Follow Up, I sent Sartin a note reminding him of what had actually happened. He replied that it wasn’t worth correcting.

Several seminar speakers told me similar stories. At one gathering, in which the group had an outing at the racetrack but few winners, Sartin explained how he caught a certain longshot winner. Only nobody had picked the horse, and nobody had bet him. One of the instructors asked him about it later, and reported that Sartin said that the tale of victory enhanced the presentation.

Often Sartin would introduce the speakers with a wonderful, though exaggerated, buildup. “Here’s a man who usually has 80% of the winners in his top two picks,” was a frequent introduction.

In a seminar, with hundreds of people awaiting your pearls of wisdom, when you’ve just been introduced as Something Terrific it takes a rare person to make a correction. The audience sees you as an august figure and you don’t want to make the emcee look like a liar. Besides, to be built up by someone you’ve admired fills you with a sense of pride and gratefulness. So when Sartin would talk about computer programs that would enable players to win 65% of the races, or profit by 60 cents on every dollar they bet, who would stand up to dispute him? No one.

“Howard was like a father figure to many of the teachers,” says one of them. “We were always vying for his approval. Looking back at it now it seems crazy, but that’s exactly the way we felt. We were always trying to please him. And if you crossed him, it could get ugly. Howard needs control, and when he doesn’t get it, the dark side of his personality comes out.”

“It’s definitely a love-hate thing with Howard,” agrees Brohamer, who remains friendly with Sartin though he hasn’t done a seminar in years. “He’s about as complex a character as I’ve ever met in my life.”

There seem to be two Sartins—the Good Doc and the Bad Doc. The Good Doc works hard at developing new material and sincerely tries to help players. The Bad Doc simply keeps most of the money and bashes anyone who disagrees with him about anything.

Still, many players who’ve used the programs say that not only are the programs good, but that Sartin has been generous with his personal time to try to help make them into winning players.

Daryl Patenaude, a California bettor, told me, “I never looked upon these seminars as sales meetings. I always knew there would be an opportunity to nail down Doc or one of the other presenters and get my questions answered. I felt they were forthright. One time, Doc even spent most of the day showing me some things up in Beaumont, and it didn’t cost me anything. I think that despite whatever Doc’s shortcomings might be, he does represent some unique thinking within the handicapping universe. He’s a real original.”

“Not only has the Doc helped me learn about racing,” says Canadian player Dean Millward, who told me he currently makes all his income from betting, “but he’s helped me realize what life is all about. I had a lot of negative stuff in my life, but he has helped me in a personal way. If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing today. I have a lot more confidence now. He’s been very generous to me.”

One thing that even detractors point out is that Sartin, over the years, has surrounded himself with capable handicappers. Among those associated with Sartin, either as guest seminar speakers, PIRCO instructors, or popularizers—in addition to Brohamer, Bradshaw, Hambleton, Pizzola, and Schmidt—have been Quinn, Dick Mitchell, Paul Braseth, Bob Purdy, Dick Quigley, George Kaywood, and Barry Burkan.

“Sartin had a tremendous eye for talent,” is how one man phrases it. “He reminds me of a coach who never could play the game himself, but he’d find people who could. He had a sixth sense of who was really sharp and who could contribute something that was unique or new. Their success would become linked with him. His strength was always in his associations.”

Eventually, though, Sartin got into disputes with many of them.

There’s little question that whatever his faults, what Sartin created and fostered has made a difference in the handicapping world. “I think that Sartin and his followers have contributed a lot to pace analysis,” says Quinn. “A lot of the people who attended seminars were poor players, and his methods improved their play tremendously. Phase III, for instance, was a very good program, showing as it did the relationships between various segments of a race. Sartin is a guy who’s presented some new ideas in an interesting way that hadn’t been presented before.

“If you look at a BRIS printout, or some of Mitchell’s, you’ll see the influence of the Sartin-style concepts,” he continues. “Later he got into a bunch of esoteric material that nobody could understand, and all this interpersonal stuff complicates any assessment of him. But I would definitely say that he has made a real contribution to handicapping.” Ken Brody, a Maryland player who used the Methodology for many years, says, “There are three areas in which I found the teachings useful. First, Howard was very strong on the psychological aspects of winning. Second, the programs helped me learn pace analysis. Third, I learned to make detailed records of how winners run their winning races.”

“What I learned from Sartin and his instructors has been how to look at a race, how to really take it apart to see how it sets up,” says Howard Kaplan, who publishes The Fair Grounds Advisor. “What I learned from them I still use as the basics of my handicapping.”

“I’ve been a rather successful horseplayer for forty years, says Ainslie, “but I never won with the frequency or consistency that I have since I started using these Sartin programs to supplement whatever else I was doing. Maybe Sartin’s not the easiest guy in the world for the average guy to understand, but those of us who’ve been around for awhile can grasp what is valid and what is nonsense. I’m no genius, but I’ve gotten nothing but good out of it. I’m an enthusiastic supporter.”

For sure, Sartin’s electrifying lectures have inspired many players. Even Hambleton, no fan of Sartin, grudgingly concedes that “Howard did try to get people to believe in themselves, and I think he was sincere about that. I felt the seminars had value, and we were doing something good. And personally, I benefitted from the name recognition I got from being one of the seminar leaders. But overall I’d have to say that he’s a very smart guy who fools a lot of people. Maybe he’s even deluded himself.”

And maybe, the fault is in ourselves. Bob Purdy was an original member of the PIRCO group. He says, “People want to just go to the window and collect. They want to turn the computer on and let it spit out the winner. But there aren’t any programs like that. What I saw in the seminars were that the people who had good skills could figure out when a horse might be advantaged or disadvantaged by the pace, and those who didn’t have good skills would have difficulties.”

Bob Rego, a California player who’s attended many seminars, agrees. “People vary in ability and talent. There are three questions you need to ask for each race: How do I select the contenders? Which paceline should I use for each horse? Does it have to be adjusted? You have to be adroit at this. The programs work—but it’s like if you have two good baseball bats and you give one to Babe Ruth and another to somebody who’s never played baseball, who do you think is going to hit the homers?”

Just because somebody bought some Sartin programs and couldn’t make any money gambling doesn’t necessarily mean that the programs are no good. Sartin never has promoted them as a “black box,” an ultimate winner-picker. “If people can’t get beyond square one,” says Patenaude, “why should they blame Sartin? He’s never put a gun to anybody’s head and forced them to buy his programs.”

In any case, the Methodology is ever changing. So I was interested in the perspective of a subscriber who is new to handicapping and attended his first seminar in 1996. “The good thing is you get certain insights you wouldn’t see, and you’re moving away from pace relationships that are visible solely to the naked eye,” he says. “But often you’re left with conflicting screens, where a horse scores well on one but poorly on another. The screens sometimes don’t back each other up, and that causes confusion.” And that’s a criticism that isn’t a new one.

As has always been the case with Sartin programs, the newest screens have their own jargon. These days you can find EXDC (normal deceleration pattern), SMUV (sustained match-up variegate), and UXR (units of energy to recover the total dream race energy). What to do? What to do?

The reader says he was surprised at a question, and an answer, that took place at the seminar. “Here we were from all over the country, and someone asked about downloading files from your hotel room. But nobody on the panel—or in the audience—knew how to do it,” he says. “It made me think that maybe some of these people weren’t really playing the horses.”

Michael Pizzola is probably not the man Sartin would choose to sum up his contributions to handicapping, but Pizzola does seem to have a knack for a phrase. He says: “Either we’re dealing with an altruistic, well-meaning fellow who really wants to help the downtrodden, and who constantly wants to refine and improve his brilliantly original methods and encourage people...or you have a con man who merely preys on people’s self-doubts and the difficulty of the horse-racing game, using massive doses of group psychology, to get their money.”

Mary Sartin says, “My father is 71 years old, and he’ll always probably remain an enigma to some people.” Then she lifted high the glass of water in front of her and proposed an impromptu toast.

“To enigmas!” she said.

General Elements Of The Sartin Methodology

The Sartin Methodology itself has been many things over the years. Among its major components (not every program includes every element):

• Use of velocity ratings (feet per second) rather than raw times

• Selection of a horse’s paceline to be used as a basis for calculations

• Use of compounded ratings (e.g., first fraction plus third fraction equals sustained pace, average of all velocity fractions is average pace, etc.)

• Use of energy distribution percentages (calculated not only for each horse, but as compared with the specific distance for each track)

• Comparisons involving each horse’s rate of deceleration

• Requirement of a computer program

• Money management recommendation is generally to bet two horses to win

Praise From Racing Authors

What do authors say, in print, about the Sartin Methodology? Here’s a sampling:

James Quinn in The Best Of Thoroughbred Handicapping: “The Methodology...works at all classes and sizes of racetracks. When [I’m asked about] the Sartin Methodology, I can respond unhesitatingly and succinctly—I think it’s outstanding.”

Mark Cramer in Win Magazine: “Dr. Howard Sartin has come up with a pace method that leads to racetrack profits. If only the savings and loans had invested in this method, American taxpayers would have been saved from their present predicament.”

Tom Brohamer in Modern Pace Handicapping: “[I would like to thank Howard Sartin], whose creative genius is responsible for many of the concepts in this book.”

Sal Sinatra in Thoroughbred Racing: Predicting The Winner: “[Sartin’s] insights in the field of thoroughbred handicapping are unmatched by any other. His research is responsible for many of the ideas presented in this book...For this, I will be forever grateful.”

Sartin’s Education and Credentials

Virtually anyone can call himself a Ph.D. “You can spend years at Berkeley, or you can get a mail-order one in a month,” says Dr. Dean Edell, who has a nationally syndicated radio show. By one estimate, some 500,000 people in the United States hold Ph.D.’s from non-accredited schools. Often these schools require little more than an application fee. When they receive your money, you receive your Ph.D.

According to several sources, Sartin’s Ph.D. comes from a mail-order divinity school that required no class work, course work, or thesis.

Though Tom Brohamer in Modern Pace Handicapping calls him a clinical psychologist and Andy Beyer in Beyer On Speed refers to him as a psychotherapist, Sartin himself has been careful never to use these terms—mainly because he has never been credentialed in California to practice any form of psychotherapy at all. Neither the Board Of Psychology (which licenses psychologists) nor the Board of Behavioral Science (which licenses other types of therapists such as clinical social workers) has any record of Sartin’s ever being licensed in the state.

SAX 04-09-97 Race 2 Dist=6 Dirt Purse $27.000

Energy Generator

Name Total Hidden Fx Med Lex 3rd ESP

Marf 169.14 66.03 65.36 68.60 32.56 31.40 E/P

Pell 170.96 64.71 66.90 68.39 32.64 31.61 PRE

Mcki 172.02 65.23 66.43 68.34 32.67 31.66 PRE

Wood 165.85 66.03 66.06 67.91 32.84 32.09 S/P

Tiny 167.71 64.60 65.86 69.54 32.18 30.46 E/P

Quee 170.83 64.55 66.11 69.34 32.27 30.66 E/P

Sartin’s programs provide a variety of readouts. This is from Quad-Rater, which has been incorporated into the Pace Launcher program.

Some Sartin Claims -- Then And Now

In Gambling Times (March 1982): “My practice is limited to so-called horseplayers and a client is cured only when his top choice is winning no less than 45% of the time with an average mutuel of $8.” Sartin now says, “This is no longer true for any but the few who are value conscious...The over-proliferation of handicapping methods, most based on mine, have reduced the average mutual for timid, non-value-oriented bettors to about $6.80.”

In The Psychology Of Winning: An Introduction to Win Therapy (a self-published 1993 booklet): “I have treated over 1800 clients...About 850 of them decided to become [investors] in horse racing...At last count, 547 are now making or augmenting their living through pari-mutuel funds; another 200 are making some profit.” In most of his recent writings, Sartin has shied away from specific numbers.

In The Follow Up (issue 39, 1993): “Over and above supporting the families that work here at O. Henry, Inc., who represent our support group and separate us from the system sellers; along with paying [Jim Bradshaw] and a few others royalties for their arduous effort; royalties, in trust, to the co-authors of Pace Makes The Race; paying lodging food, travel, and other seminar expenses; plus fees to key personnel and the editor’s cut from The Follow Up, I make very little.” Sartin says he has not taken any salary in the last year, saying he lives on social security and what he makes from wagering.

Sartin And His Statistics

We checked the second edition of Pace Makes The Race, since presumably errors in the first edition that were simply typographical would have been corrected, and discovered these in sections written by Sartin:

P 2: “...in 1959, the two lowest odds public choices won 53% of all races. As a direct result of the information age, that figure has declined to a current 49.7%.” A computer check of every race at every major racing circuit in 1994-95 showed that the top two public choices actually accounted for 55.1% of all wins.

P 138: “More important, especially in California, is the fact that 37% of all winners are off more than 21 days between races.” We checked the results of every southern California race run in the past 3 1/2 years. Excluding first-time starters, nearly 57% of the winners had been idle for more than 21 days.

P 155: “78% of all longshots, horses paying in double figures, are going up in class.” Out of 3,356 double-figure winners in California exclusive of first-time starters, only 23.2% were rising in class.

The Sartin Methodology Today

According to Sartin, a player should narrow a race to no more than five contenders using the best of the last three comparable DRF Speed Ratings plus track variant, adjusted for track-to-track, with no other subjective procedures. Then, let the software do the rest.

His latest program is Pace Launcher. Version IV sells for $479, with Version V scheduled for future release. According to Sartin, “Hidden within the algorithms that produce the readouts...is virtually everything viable in all other programs...” He calls Pace Launcher “the winningest methodology ever.”

Sartin’s next major seminar is scheduled for Las Vegas Nov. 7-9.

Upcoming is a new one-hour video along with an audio cassette series.

For further information, Sartin can be reached at 909 845-XXXX.

|